News

Published June 3, 2020

As COVID-19 continues to spread across Texas and the nation, scientists from the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering & Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Houston have created a mapping tool for determining which populations in Houston and the city’s surroundings appear most vulnerable to the infection.

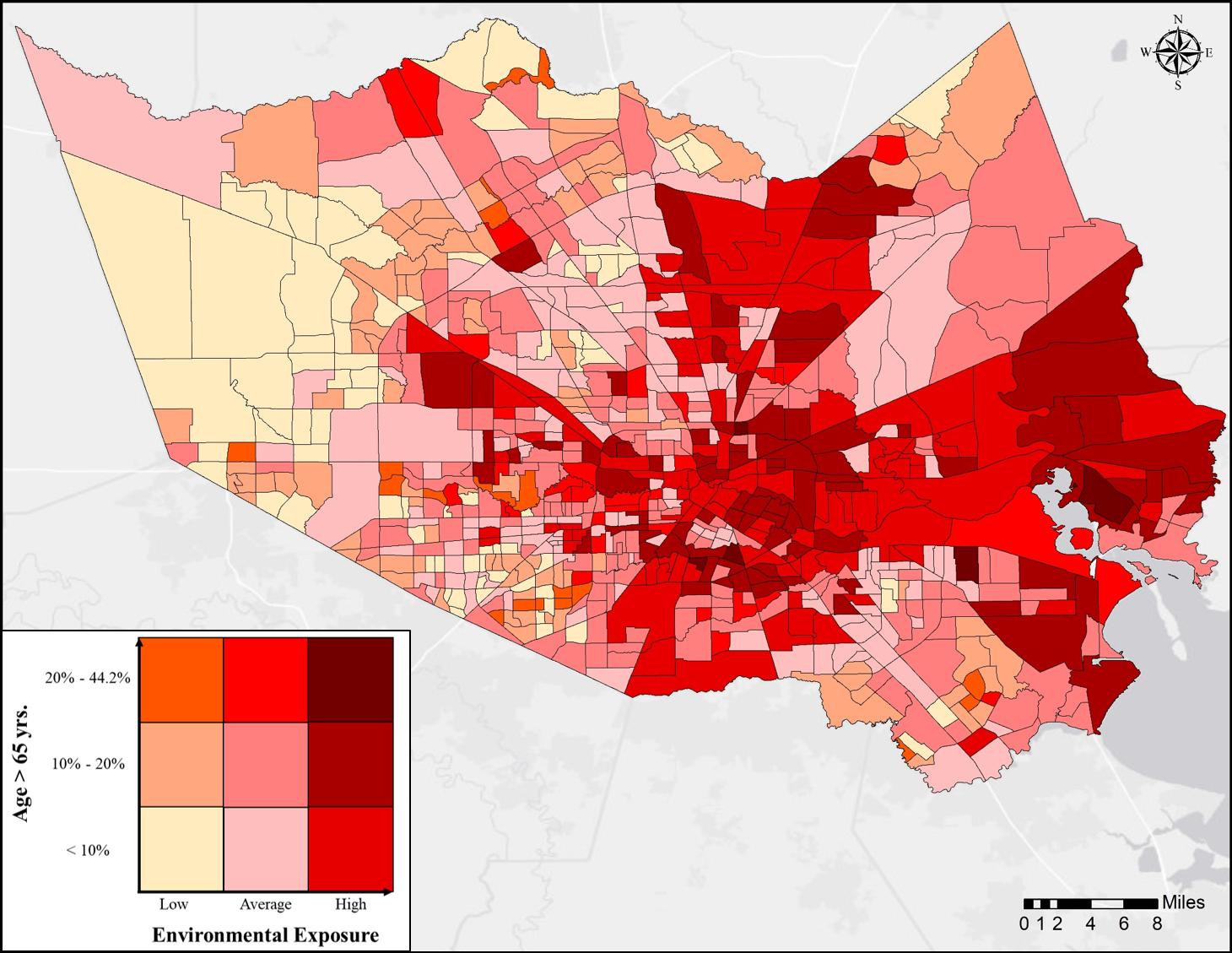

The tool takes a holistic approach to health, with access to medical care, potential exposure to pollutants, and medical insurance coverage being among the factors taken into account. Overall, the most at-risk areas are in the east and northeast areas, especially those clustered around industrial areas and high-traffic waterways.

“The map offers a comparative look at vulnerabilities across Harris County, and could help policy makers determine how to allocate coronavirus tests and health and safety resources,” said Amin Kiaghadi, a research associate at the Oden Institute and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Houston.

“I'm really interested to see how decision makers look at these maps,” he said. “They can say ‘this specific area is vulnerable to many different things—people living there have lower income, they have or they don't have access to the medical care— and that can change the way that they distribute the resources.”

Kiaghadi conducted the research with University of Houston’s Hanadi Rifai, a professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Winston Liaw, a professor of health systems and population health in UH’s Medical School.

Their research is posted as a pre-print study at MedRxiv.

Kiaghadi’s usual research focus at the Oden institute is how floodwaters, such as hurricane storm surge, can spread contaminants as they flow through an environment. With the outbreak of COVID-19, he said he saw an opportunity to apply techniques he had learned studying one type of natural disaster to another. That involved using the same database architecture to organize data related to COVID-19 vulnerability.

“We already had a lot of knowledge and experience working with this sociodemographic data, and population vulnerability to the flaws in the environment and exposure,” he said. “So we felt like, this is totally related to our research, so why not explore what it means?”

Just two weeks after starting the project, they had their maps.

The map area is divided up into 786 polygons (census tracts) based on census data, with the researchers taking numerous health factors into account that may influence vulnerability to illness due to COVID-19.

“We believe that if you're exposed to some chemicals for a long time or you were living in an area with bad air quality, that can affect your immune system long term and then make you more vulnerable to a disease like COVID-19,” Kiaghadi said. “So we decided to take a new approach here and show that these factors should be considered.”

The statistical framework underlying the map includes 46 different variables in five categories:

1) People with limited access to hospitals and medical care. 2) People with underlying medical conditions. 3) People with exposures to environmental pollutants. 4) People in areas vulnerable to natural disasters and flooding. 5) People with specific lifestyle factors, like obesity, drinking and smoking.

The variables for each census tract were collected from publicly accessible national, state and county databases.

Overall, the highest risk areas are in poorer communities, especially those near the Houston Ship Channel. The populations with the lowest risk are in the far west areas of Harris County, which are richer and away from the most industrialized parts of the county. About 17% of the entire population of Harris County falls into at least one risk category.

In addition to risk factors, the researchers also used the map framework to investigate which areas would be most susceptible to infection, illness and death if COVID-19 transmission rates were on par with those observed in New York, China, and Italy. But Kiaghadi emphasizes that these numbers aren’t diagnostic and should only be treated as a means of comparing relative risks across populations.

For more info contact: Johnny Holden Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences jholden@oden.utexas.edu